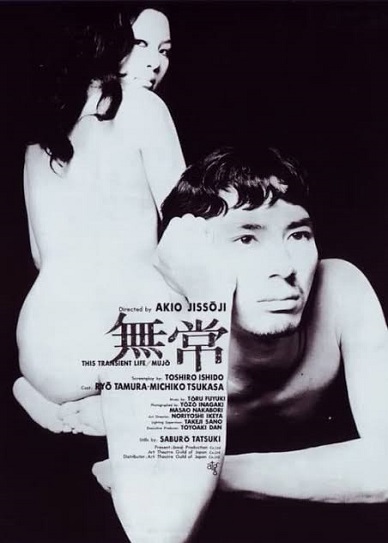

This Transient Life (1970)

Free Download and Watch Online 720p/1080p Bluray Full Movie HD

The Midnight Eye reviews of Jissoji’s films, ostensibly a very well written piece that is almost the only critical source readily available, reads a spiritual importance that should place Jissoji next to Dreyer and Bresson, it considers them successful films on Buddhist thought. Stylistically they couldn’t be more different but what about the content, does Midnight Eye horribly misrepresent their intention?

“life and death are a great matter, transient and changing fast”

This is a mantra to the films. In all three of them, Mujo, Mandala, and Uta, Jissoji grapples with basic tenets of Buddist thought. Impermanence, emptiness, the practice and ethos of the faith, he calls these into question. For Bergman that question was posed and declined, it was the spiritual self doubt, the existential cry in an indifferent universe that mattered. The important thing to note as we enter into a dialectic with these films is that Jissoji, who like Bergman was brought up in a religious family, made films for the Art Theater Guild. Like his mentor Nagisa Oshima and like Oshima’s mentor Yasuzo Masumura before him, he seeks out the individuality of his protagonists in a madness that defies society and liberates from it, in a youthful rejection of the old and stale. Jissoji’s films then are not profound examinations of faith but radical portraits of rebellion.

Mandalas are diagram symbols used as objects for meditation by esoteric Vajrayna traditions, they represent a sacred space for the concentration of the mind. So what is revealed to take place inside this sacred space, how is our concentration challenged or rewarded? First, Jissoji’s thesis.

The moral code and the transience of life.

Masao’s confrontation of the Buddhist monk in Mujo where he expounds on his personal realization on the nature and absence of good and evil, heaven or hell, and the nothingness of nirvana is an insurmountable attack that advocates liberation by smashing of moral boundaries, it promotes the pleasing of the will and the senses. The path of pain and misery Masao’s choices leave behind him are excused because he wasn’t alone in doing them. If he can pervert another, isn’t that equally the other’s fault for allowing it to happen, the movie asks. And if life is transient, as the title says, why shouldn’t we give in to our pleasure, devote ourselves to it at the cost of everything else?

I love how in all three films the crucial turning point is consumated from behind masks, with something of a bestial or mystical nature. These moments are an apotheosis for Jissoji’s cinema.

The game of seduction between brother and sister in Mujo is enacted with masks, the camera losing and finding them again behind a labyrinth of walls and panel doors before the incestuous ravishing can be consumated. This ritual dissolution of the self permits the forbidden, the taboo can be brought down by the adoption of another face.

Beyond the thematic reaction, thought has been truly paid here. The masquerade is one, Buddhist tenets turned into visual clues is another. In Mujo, life was transient and so was the camera, life is in constant flux and so the placement of the actors often varies tremendously from shot to shot. In Mandala, Jissoji distorts space with widescreen lenses, literally creating the sacred space of a mandala. When Shinichi begins to live outside time, the movie turns black and white. In Uta, the total awareness of the present moment is rendered with the ticking sounds of a clock, and when the houseboy sits down to eat his tasteless grub, we get close shots of his throat swallowing. The boy maintains an unruptured state of concentration, and the camera follows that state.

I’ve tried to paint a vivid picture without many specifics (the films are rich in material to discuss) that hopefully places the films in a context. Jissoji’s New Wave calls moral codes into question, considers meditation a practice of death, and the spiritual pursuit of liberation a terrible folly.

Buddhism is the recipient of his scathing New Wave and Buddhist thought is formulated only to be rejected, to receive scathing contempt or bitter irony.

From a spiritual standpoint I disagree, for one the “nothingness” of nirvana is not a rejection of consciousness as Mujo posits, but rather a supreme consciousness, a true perception of the world as impermanent and everchanging. If life is like playing the piano, the enlightened doesn’t stop playing it to become absorbed with the self, but, having tuned it to perfection, plays every note in harmony. And the moral code of good and evil, the “sila” of the Buddhists, is not a restriction of laws but rather a realization that certain acts further our misery, others free us from it.

But as New Wave I can’t deny the power of these films, and more, opposed to Godard’s contemptuous attacks on the bourgeoisie or Wakamatsu’s liberation from society through nihilism, this is thoughtful cinema that raises valid points, New Wave expression that feels vibrant and alive.

To return to the opening statement found in the Midnight Eye review, there’s room enough to discuss Jissoji in the context of Dreyer. A more apt comparison, is to discuss him in the context of his peers. That he remains, along with Kazuo Kuroki, probably the most esoteric of the Nuberu Bagu is telling. Cinema is not a casually irreverent affair with the fashionable in films like Uta, it’s difficult and demands we rise to the occasion, to join the discourse and maintain our own state of concentration.

Posted on: November 25th, 2019

Posted by: king